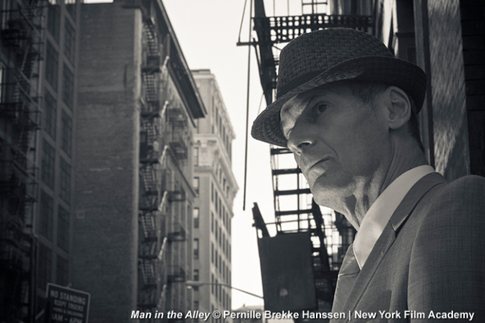

Does a Degree in Photography Make You a Better Photographer? Guest post from New York Film Academy2/19/2013 Originally posted on the PhotoResourceHub.com site, it's an interesting perspective on a question that often comes up... by Skip Cohen There's been a lot of great discussions over the years on the advantages of a formal education in photography. Some of the finest photographers in the world never attended a full time educational institution with the intent of majoring in any aspect of imaging. But that's exactly my point today. Photography is no longer a stand-alone art form or vocation, we call it "imaging", which is far more extensive. "Imaging" encompasses so many different aspects of art, technology, marketing and business. In order to stand out from the Uncle Harrys I write about all the time, you've got to have a solid skill set and yet, by definition, millions of people consider themselves photographers. On the website for the New York Film Academy they wrote: "Photography is an art form, a way of seeing the world; it’s also the most popular hobby on the planet. But great art can only be created through the vision of an artist who has mastered the broad technical and aesthetic challenges that require every photographer to make dozens of split-second decisions about shutter speed, aperture, ISO, composition, focal length, gesture, and the precise moment of exposure when capturing a photograph." Recently I was approached by one of their staff members who asked if he could write a guest post on the topic. I approached the idea with a great deal of cynicism and was pleasantly surprised by what I received. Here it is completely unedited and terrific food for thought. By Russ Klettke - consultant writer at New York Film Academy. There are two points of controversy around photography that have been around for a long time. One asks whether photography is a fine art – under the same umbrella as painting and sculpture, for example -- and the other is whether or not a university degree is required to become a photographer. The answer to both is “it depends.” And perhaps, “it’s a matter of degree.” Certainly there are fine photographs that are worthy of the fine art designation. The work of Ansel Adams, Matthew Brandt, Adolph de Meyer, Edward Steichen and Gertrude Käsebier might come to mind (the latter three are part of Alfred Stieglitz’s famous collection donated to the Museum of Modern Art in 1928, when photography first achieved top-tier art world attention). Perhaps what keeps the controversy alive today is that fine art photography is a mix of what someone simply observes and what they do to represent that observation. This debate is intensified by the easy manipulations by way of digital technologies by Brandt and others – in ways that Ansel Adams, with old fashioned darkroom burning and dodging, never imagined. But does a photo snapped by an amateur’s smartphone qualify as art if it’s seen by millions on Pinterest or if it goes viral via Twitter or Facebook? Ultimately, the answer is in the eye of the beholder. Interest and popularity are sometimes a measure by which we judge artistic merit, but it boils down to judgment. The matter of motorcycles in the Guggenheim museum (“The Art of the Motorcycle,” 1998) and whether or not the design of vehicles constitute art found its own debate – even though the wildly popular exhibit drew more than 300,000 people to its three-month exhibit. The critics sniffed, but it was the most popular show ever at the iconic museum. Where it comes to studying photography, there are many opinions of whether post-secondary education is required and to what degree that study it makes for a talented photographer. As an educator, I am of course biased in favor of education, and I believe that more is more. The person who has technical skills can do well in many forms of photography. But the person who has a deeper understanding of the natural world, the human condition, and even world geopolitics will have advantages as both a photographer and as a business person (a large portion of photographers are self-employed, and therefore need to manage their marketing, bookkeeping and profit/loss considerations). The breakdown is often made according to career objectives. A photographer who is interested in portrait work (schools, weddings, etc.) is ideally a solid technician with a personality that is fit for the job. A year’s worth of very technical study may be adequate, while an apprenticeship with an established photographer is probably as or more important. The portrait photographer needs to be confident, and for some that confidence comes with a degree. Photojournalists are in a different category. They have to identify visual representations of news and often themselves study alongside writers for at least a portion of their education. A nature photographer needs to understand botany and biology; a financial news photographer should at least know how mortgage crises lead to foreclosures; a sports photographer should have insight on the physical and emotional drama of athletics and the sports industry, on and off the court. A four-year degree or master’s in fine arts are generally valued by news organizations, if not required of photographers. Then there are commercial photographers, working in advertising and corporate communications. They are on the same team as highly proficient marketing and public relations people, and have to be seen as intellectual peers as well as good photographers.  Almost all journalism university programs include digital photography schools, and where you study can make a difference in several respects. One is the emphasis on living with your camera. Some institutions bring you into actual photo classes by your sophomore or junior years, while other place a camera in your hands at freshman orientation. Another component is your surroundings: the physical location of a school will have a lot to do with what you learn to shoot. A school set in a rural setting might lead you to a career in outdoor photography, perhaps focusing on landscapes or agricultural themes, while a city location would provide a very different experience. Consider also the broader scope of the university: if it includes a robust phys ed program and proximity to college or professional sports teams, you might end up as a sports photographer. A vibrant performing arts academy will instead expose a student to actors, singers, dancers and those around them. In general, the learning experience is holistic and can set a path for the first phase or entirety of one’s career. So as with most controversies, the questions around photography – Craft or art? Technical training or university degrees? – are never fully resolved. It is up to the prospective student to consider their goals, look at their options then make a decision. As a photographer and educator, I can assure you it’s a great ride when you enjoy the path you take. By New York Film Academy Photography School Staff Member So the controversy will just continue, but I did love the perspective this educator took. If you've got an interest in checking out the variety of educational opportunities, they offer a wide variety of programs from a 1 week workshop to a full Masters of Fine Art degree. One thing I do know for sure - there's no such thing as too much education. Photography/imaging is a career path where you never stop learning! Note: Russ Klettke writes on arts education, health, nutrition, sustainable architecture and planning, plaintiff law and real estate. He received a degree in magazine journalism and economics from Syracuse University and lives in Chicago. Individual Photo Credits as shown. All images taken by students at NYFA.

1 Comment

yosimmitysam

4/21/2013 04:54:39 am

you are bullshiting

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

November 2016

|

© 2019 Skip Cohen University

RSS Feed

RSS Feed